- 28 Sep 2025

- 0 Comments

The moment a carefully chosen gift is presented—whether for a holiday, a wedding, a birthday, or simply as an act of kindness—is universally recognized as a profound social interaction. We often focus on the recipient's delight, yet the true magic of this exchange is its surprising benefit to the giver. The decision to bestow a gift is more than a social custom; it's a powerful act of self-care and a direct boost to one's own well-being. From a neurological perspective, the moment you give a gift, you are simultaneously unwrapping a 'present' of biological rewards for yourself.

The Dopamine Reward: Unpacking the Helper’s High

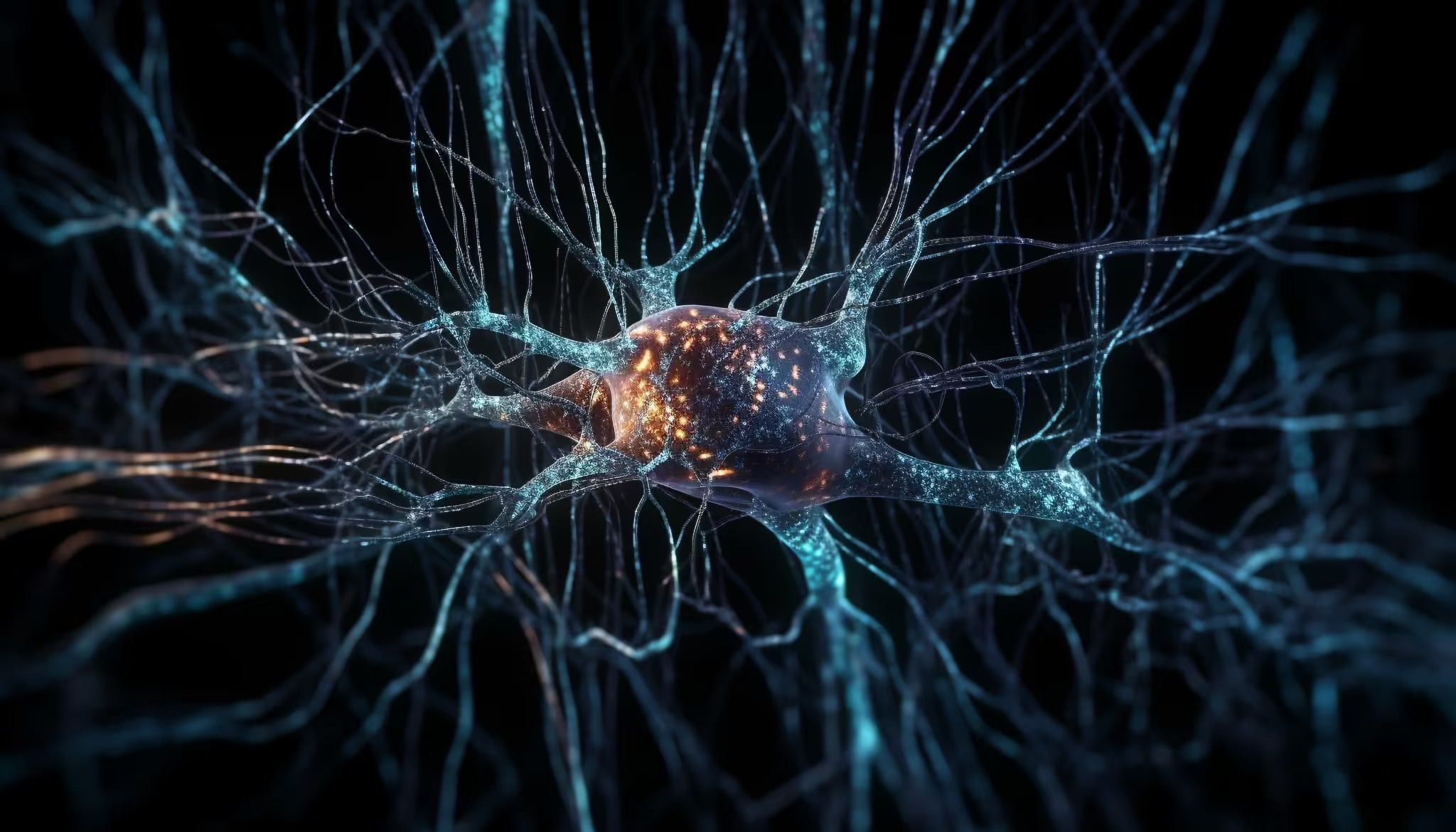

The immediate rush of satisfaction from giving is not merely sentimental—it is hardwired into our neurobiology. The brain is equipped with a sophisticated reward system, the mesolimbic pathway, which is designed to reinforce behaviors essential for survival.

When we perform an act of altruism, such as handing over a thoughtful gift, this pathway springs to life. Researchers have used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to observe that the brain’s pleasure centers—specifically the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the nucleus accumbens (NAc)—activate when individuals contemplate or execute charitable acts[1]. These are the same areas that fire up in response to primary rewards like food, exercise, or sexual activity.

This surge triggers a release of dopamine, the key neurotransmitter associated with pleasure, motivation, and positive reinforcement. This measurable feeling of warmth and satisfaction has been aptly coined the “helper’s high,” a real phenomenon that motivates us to repeat generous actions[2]. This neurological mechanism suggests that altruism is not entirely selfless; it’s an evolutionarily beneficial trait that our brains reward us for practicing, creating a positive feedback loop of generosity.

Oxytocin and Empathy: Strengthening the Social Fabric

Beyond the immediate euphoria of dopamine, giving triggers the release of other chemicals crucial for long-term emotional health, most notably oxytocin. Often referred to as the “cuddle hormone” or the “prosocial hormone,” oxytocin is essential for social bonding, trust, and empathy.

When a gift is exchanged, the resulting social connection reinforces the relationship between the giver and the recipient. The release of oxytocin helps to solidify this bond, directly enhancing feelings of trust and reducing social anxieties[2]. This effect extends beyond close relationships, contributing to a broader sense of group cohesion and belonging. From an evolutionary perspective, an oxytocin-fueled desire to connect and help others is a mechanism that promotes collective well-being and survival.

Furthermore, the process of selecting a thoughtful gift relies on empathy—the cognitive ability to imagine another person's mental state or feelings. This requires the giver to step out of their own perspective and anticipate what the recipient genuinely wants or needs. This exercise in perspective-taking has been shown to increase neural activity in brain regions linked to social decision-making. When we successfully identify with the recipient's joy, our reward system is activated, reinforcing the empathic behavior.

The Cortisol Effect: Stress Reduction and Longevity

The benefits of generosity are not limited to fleeting feelings; they extend to significant physical health markers, acting as a powerful antidote to chronic stress.

Chronic stress is regulated by the hormone cortisol, which, when consistently elevated, can suppress the immune system and contribute to various health issues. Acts of giving and volunteering are directly associated with lower levels of circulating cortisol and a noticeable reduction in blood pressure[2]. This positive emotional state acts as a powerful buffer against the daily psychological and physiological demands of life.

The long-term health implications of this stress reduction are compelling. Longitudinal studies examining altruistic behavior, particularly volunteerism, have revealed a strong correlation between generosity and improved physical health. Research indicates that individuals who frequently engage in altruistic behavior report greater satisfaction with life, demonstrate reduced rates of depression and anxiety, and even exhibit increased longevity[3]. This suggests that the psychological shift—from focusing on one's own worries to focusing on bringing joy to others—is a form of emotional regulation that leaves the giver feeling more calm, grounded, and ultimately, healthier.

Whether it’s a simple token or a grand gesture for a major life event, the act of giving is a beautifully balanced social contract. The recipient receives an item, and the giver receives a cascade of positive neurochemical and psychological benefits that improve mood, strengthen relationships, and contribute to a longer, healthier life. The next time you set out to choose the perfect present, remember that the act of giving is one of the most profound and scientifically rewarding gifts you can ever bestow upon yourself.

[1] The Neurobiology of Love and Altruism: Converging Pathways of Social Reward and Human Survival

[2] The Neuroscience of Giving | Psychology Today

[3] Altruistic behavior: mapping responses in the brain | NAN - Dove Medical Press